Freight lines ridden: Burlington Northern, Denver and Rio Grande Western, Southern Pacific, Milwaukee Road, Western Pacific, Union Pacific, Louisville and Nashville, Seaboard Coast Line, Southern, Penn Central, Erie Lackawanna, Delaware and Hudson, Boston and Maine.

Freight lines ridden: Burlington Northern, Denver and Rio Grande Western, Southern Pacific, Milwaukee Road, Western Pacific, Union Pacific, Louisville and Nashville, Seaboard Coast Line, Southern, Penn Central, Erie Lackawanna, Delaware and Hudson, Boston and Maine.

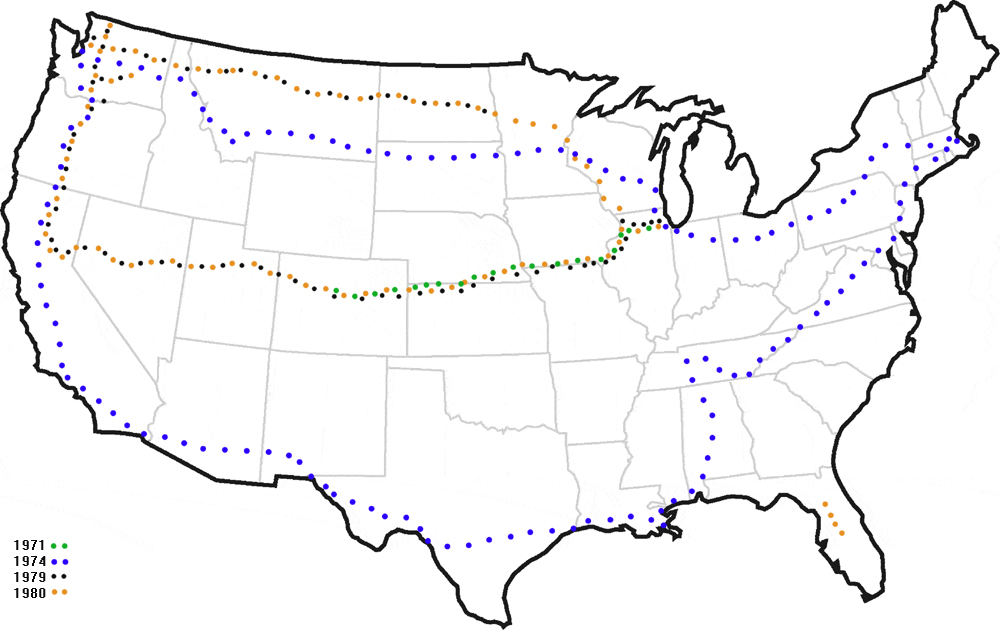

THE JOURNEY

My introduction to train-hopping took place in August of 1971 on a Denver to Chicago freight train. Alone in a boxcar, I watched the flickering lights of the prairie towns shimmer like grounded galaxies, appearing and disappearing as the train rumbled through the warm Midwestern night. During a stop in a Galesburg, Illinois train yard, a soot-blackened face emerged from the darkness and asked, in voice caked with dust, about the destination of the train. It was a brief moment between a row of freight cars but one that stuck in my memory. The blackened face, the gravely voice, and the hard life it embodied, haunted me and, ultimately, became the inspiration for documenting the lives of the handful of men who carved out a life along the tracks.

Year after year I often encountered the same men. Once, during the winter in a Florida jungle, I shared a bottle with a tramp and met him the following fall upon waking up in an apple orchard in Washington state. He was picking apples while I was crawling out of my sleeping bag. I stumbled upon another tramp in Oregon who I’d spent time with in Nevada the previous year. He was on a drunk and passed out between the rails on a siding. Waking him up and persuading him to get off the tracks was disquieting for both of us. And Teto, the industrious tramp who fashioned sheath knives in his camp. The second year I spent with him, he offered one of his knives to me. I declined because I knew it was a source of income for him. Now, though, I wish I’d accepted his offer. One of his handmade knives would, indeed, be a treasure.

There’s plenty of stuff the camera can’t do, like capturing the pungent odor of creosote and diesel fuel that permeates the yards, or the dust-streaked sweat of men who spend their lives living outdoors, or coffee boiling in a tin can over an open fire in the morning. And the night-long slamming of train cars in the yards, followed by the straining of diesel engines and the banging of couplings when the train takes up slack. And of course, the deafening roar of steel wheels turning beneath a boxcar floor. Then there’s the tramps like Whistlin’ Jack who didn’t cotton to picture-taking. His crusty grin revealed only a single tooth, and all I have is the remembrance of the two of us sitting around his fire while Jack spat every so often onto the glowing coals, each spit hissing as it hit the embers, sending a puff of ashes into the air. His image, along with others, have vanished and scattered like so many ashes by the side of the tracks.

Along the way, there were plenty of close calls; some, too close. Poodle Frenchy was stabbed to death just moments after I left him at his camp on the Columbia River. Another time, Bill, a massive six-foot-plus tramp passed out in my arms late one night as we were climbing into a boxcar in Wishram, Washington. I was able to ease him onto the track ballast where he slowly recovered from his seizure. Then there was the time the train came close to derailing while racing across a South Texas desert. The boxcar directly in front of mine caught fire and was dragged along unnoticed for way-too-many heart-pounding miles. And a lesson was learned the night I boarded a boxcar directly behind the units, and diesel smoke quickly filled the car, forcing me to climb out of the open door and onto the roof and work my way down the moving train. Missteps while riding the rails are unforgiving. Even the best of tramps occasionally meet a tragic end beneath the wheels of a train, which, incidentally, happened on a spur-line one night while I was up in apple country along the Canadian border. There were many other incidents, and, looking back, all I can say is I was lucky in so many ways. And I can confirm from experience that spending a night or two in a small town jail is not all that bad. The narrative, though, belongs to the tramps, for in their world I was just passing through.